by C. Liegh McInnis

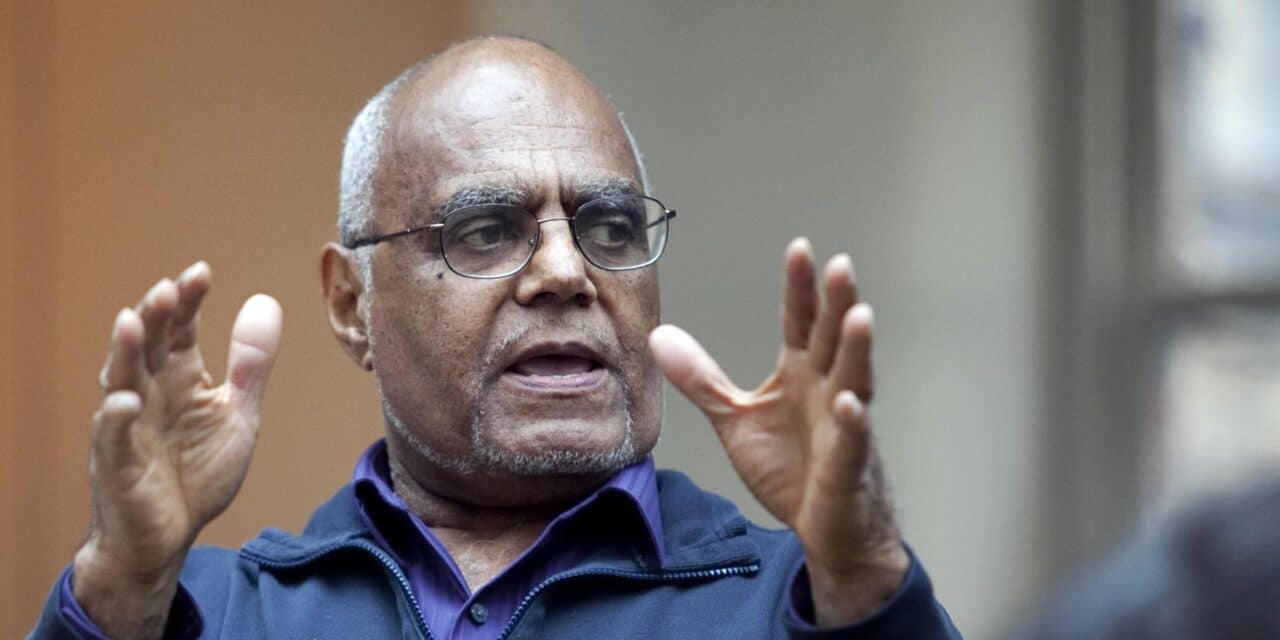

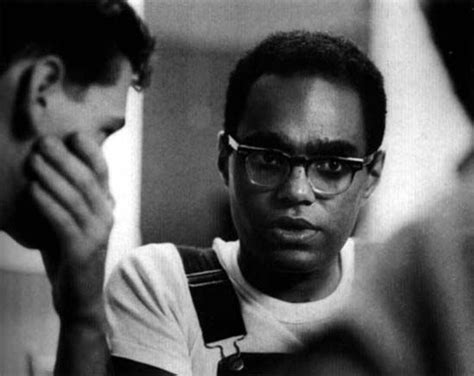

I often wondered how someone as gentle as Robert “Bob” Moses could be so powerful. We don’t usually associate power with gentleness. Yet, Moses was one of the most gentle, kind, and soft-spoken persons I ever met. Leaders, especially Civil Rights leaders, are traditionally fiery not tranquil. It took me a moment to realize that determination can be both fiery and tranquil, especially when determination is covered and guided by love. But, for Moses, love is not an attempt to placate white folks. As Moses stated to award-winning poet, novelist, and literary theorist Robert Penn Warren during an interview for the Who Speaks for the Negro?, the majority of the members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) did not agree with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, philosophy that “they have to somehow love the white people that they are struggling against.” For Moses, love is the natural energy of the universe, like light, that is perpetually working and expanding to create beauty through order, harmony, and justice. Thus, love is no respecter of person; yet, it willingly feeds and serves all who have the capacity to be just. Moreover, the inner peace of morality, of longsuffering, of seeing the humanity in all peoples, and of knowing that hatred is a cancer that kills human beings one cell at a time is what fueled Moses’ gentleness. In my short, twenty-plus years of knowing Moses, I never heard him raise his voice; yet, I witnessed him command a room with a love powerful enough to baptize us all. I saw all types of people go silent in awe for what he did, what he was doing, and what he was going to do because he was always in the process of teaching us how to love/live better today than we loved/lived yesterday. However, for Moses, love is a plan. Love is an action verb. Love is critical thinking. Love is loving yourself enough to force others to love you. Love is not fear. Love is not pride. Love is not turf wars. Love does not desire to be the center of attention. Love is not a resume bullet point. Love is not status. Love is not working to have white folks think highly of you. Love is not lust. Love is not avarice. Love is justice. For Bob Moses, love is justice. And, his work with SNCC, the Algebra Project, and the generational fruit that his work bears are all testaments that innate to love are critical thinking and work. As such, his life is a blueprint for black folks to liberate themselves from white supremacy (police brutality, discriminatory hiring and promotion practices, discriminatory housing practices, discriminatory education policies, voter suppression, discriminatory charging and sentencing, and more) by using their own resources and by forming alliances with others who can help but not dictate the goals and methodology of black sovereignty.

Moses was inspired to get involved in the Movement because he saw a group of North Carolina A&T University students sitting-in a Woolworth in 1960 demanding to be served, and he thought to himself, “They look like I feel.” If a picture is worth a thousand words, then those students resonated the pride, anger, frustration, and resolve that burned in Moses. That was one of the seminal moments that sparked Moses into action. By then, Moses already had earned a BA in philosophy and French while playing basketball at Hamilton College and an MA in philosophy at Harvard. But, his mother’s death and father’s illness caused him to leave his PhD program and return home to New York City. It was during this time that Moses became a tutor for Frankie Lymon of the Teenagers and was introduced to African-American towns and communities across the nation. This experience exposed him to the segregated yet well-ordered African-American lives that shared a common history and culture. It affirmed in Moses the beauty and power of black folks and his understanding that they just needed to be given the tools to do nationally what black folks had been doing locally for years—surviving by turning hell into livable. The combination of his family upbringing, his academic studies, his brief time in Europe, and his time traveling the country with Lymon confirmed for Moses that black folks were all the leadership that they needed. They just needed to be taught to see themselves as their own liberators. Thus, regardless of his work or organization, the core of Moses’ productivity remained teaching black folks how to free themselves.

He initially began in 1960 by traveling to Atlanta, Georgia, to work with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), but there was little grassroots work being done there. Similarly, the NAACP didn’t appeal as much to Moses either because the bulk of their work was litigation and not direct action. To be clear, many members of the NAACP were involved in direct action, but it was usually in connection or collaboration with other organizations. Then, in 1960, Moses became a field secretary for the SNCC, and went to Cleveland, Mississippi, to work with NAACP veteran Amzie Moore who actually put voter registration on SNCC’s agenda, but the black folks in Cleveland were not ready for a mass movement. So, Moore connected Moses with another NAACP veteran Curtis Conway “C. C.” Bryant in McComb, Mississippi, and that’s when they started moving mountains as Moses met two young men, Hollis Watkins and Curtis Hayes, who were eager to work. Under Moses’ leadership and with help from too many folks to name, such as the great strategist Ella Baker, SNCC developed two programs of work: direct action led by Diane Nash and Marion Barry and voter registration led by Moses and included greats, such as Fannie Lou Hamer. This dual-threat shook the confederate fibers of Mississippi and the South, eventually bringing Jim Crow to its knees with the help of so many, such as Dorie and Joyce Lander, Vernon Dahmer, and Clyde Kennard, just to name a few. But, the sacrifice was great, as Moses and others were brutally beaten, while others were killed. In 1963, Moses, Jimmy Travis, and Randolph Blackwell were driving from Greenwood, Mississippi, when shots were fired into their vehicle, hitting Travis who was hospitalized but survived. However, many did not survive, including Dahmer, Kennard, and fifty-six-year-old farmer Herbert Lee who was killed by a white state legislator E. H. Hurst in front of several witnesses for attending a voter registration class organized by Moses. As expected, Hurst was cleared of all charges by an all-white jury. While these types of assaults and killings were normal, the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in 1964 impacted the nation in a way that only the murder of Emmet Till had in 1955. In the face of this type of terror, Moses became the first African American to file assault charges against a white person. Of course, the white person was acquitted of the charges, but Moses’ actions sent a message to blacks and whites that a new day was dawning in which fear would no longer stop black progress. Simultaneously, Moses was helping to organize the 1964 Freedom Summer Project and co-founded the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), which served as the umbrella group for SNCC, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), NAACP, and SCLC to work collectively on the Freedom Summer Project. While doing this, Moses and others co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged the all-white regular Democratic Party delegates from Mississippi at the party’s 1964 national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Because the Democratic Regulars had for decades excluded African Americans from the political process in Mississippi, the MFDP wanted their elected delegates seated at the convention. Their challenge received national media coverage and highlighted the Civil Rights struggle in the state, with one of the highlights being Hamer’s famed “I Question America” speech. Four months later, Hamer gave her noted “I’m Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired” speech in Harlem, NY, with Malcolm X aka el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz. The rise of Hamer from a sharecropper to a major Civil Rights voice highlights Moses’ and SNCC’s ideology and methodology of helping everyday people become the voices and policymakers of their movement. Unfortunately, by 1966, Moses was forced to flee the country because he was notified that he had been drafted even though he was five years too old for the cutoff to be drafted. Living in Canada and Tanzania for close to ten years, Moses returned to America in 1976, pursuing graduate work in mathematics at Harvard.

After being notified by his daughter that a local high school did not offer Algebra, Moses began teaching Algebra at a public high school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By 1982, Moses was teaching Algebra at Lanier High School in Jackson, MS, and developed the Algebra Project, which uses math to teach critical thinking, social awareness, and activism to give the poorest children with the traditionally lowest math scores the tools needed to change their circumstance. The Algebra Project was Moses’ way of dismantling what he called “sharecropper education,” in which black folks were educated just enough to be the perpetual labor base for white supremacy. He asserted that Algebra is a critical “gatekeeper” subject because mastering it is necessary for middle school students to advance in math, technology, and science; attending college is impossible without Algebra. I know this firsthand because my sister, Dr. Elizabeth McInnis who has a PhD in educational technology, is a product of the Algebra Product. According to Diane Cole’s “The Civil Right to Radical Math,” “At Lanier High School (Jackson, Mississippi), 55 percent of the students in the Algebra Project’s curriculum passed the state exam on the first try, compared to 40 percent of students taught with the regular curriculum. More students at junior high school sites who followed the Algebra Project curriculum scored higher on standardized tests and continued to more advanced math classes than did their schoolmates who followed standard curriculum.” Yet, still not resting on his laurels, Moses developed the Young People’s Project, which features local artists and educators, such as Jolivette Anderson aka The Poet Warrior, to help engage students in their learning process. YPP uses mathematics literacy as a tool to develop young leaders and organizers who radically change the quality of education and quality of life in their communities so that all children have the opportunity to reach their full human potential. According to Cole, “At its peak, the Algebra Project has provided help to roughly forty-thousand minority students each year. Contributions include curricula guides for kindergarten through high school, the training of teachers, and peer coaching.” As such, everyone should have a copy of Moses’ Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Projects, which can be purchased here. While my Pops knew and had crossed paths with Moses, it was only after meeting Anderson and then local community activist Derrick Johnson in 1996 that I worked on various events and programs coordinated by Moses. To be quite honest, had it not been for Anderson and Johnson, I, who was only interested in publishing poems and short stories, would have probably never done much of the community work that I’ve done. Other than teaching creative writing at the juvenile youth court center because my Pops was the senior counselor who forced me to do it because “he said so,” much of my local community work comes through my relationship with Southern Echo, YPP/Algebra Project, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, and the National of Islam. Fifty percent of that work is connected to the work and legacy of Moses.

At times like these, it is easy to be overly general and sweeping in our remembrance of someone. For me, it is the often simplistic distinction that I make between SNCC as a grassroots organization of the people and the NAACP as a more bureaucratic, top-down organization. And, the truth is somewhere between those poles. Yet Moses (associated with SNCC) and Medgar Evers (associated with NAACP) were so intelligent and so loving that they defied simplistic definitions. As such, both were courageous foot soldiers who had the minds of generals. As leaders, neither ever asked anyone to do something that they had not already done. When Moses told people to be prepared to go to jail, it was because he had already been. When Moses asked folks to be good students, it was because he had already mastered Civil Rights warfare. And, Moses, like Evers, shined most in his ability to connect with, inspire, and teach common folks how to lead their own movement. Unfortunately for Evers, while the local branches have always been and remained powerful, too much of the NAACP national leadership, for years, was disconnected from their local branches. However, it is interesting that the current national leader of the NAACP, Derrick Johnson (the same aforementioned former community activist), has worked to illuminate and support its local branches in ways that hadn’t been done for years. This is because Johnson is fruit from the Moses tree by way of Watkins, that same former SNCC Field Secretary from McComb who later co-founded Southern Echo with another SNCC worker Attorney Mike Sayer and a local activist Leroy Johnson. Derrick Johnson, along with Brenda Hyde and Nsombi Lambright, was one of the first people that Watkins, Sayer, and Leroy Johnson mentored and employed to be the next generation of community organizers and leaders. Thus, through D. Johnson and others, Moses’ work will continue as D. Johnson has continued to pay it forward by investing in the local NAACP branches, by investing in the NAACP Youth Chapters, and by founding Mississippi Black Leadership Institute (MBLI) as another way to educate and develop local young black leadership that is beholden to black people and not white money. Additionally, Hyde continues to hold a leadership role in Southern Echo and Lambright became the first African-American woman to lead a state ACLU chapter before taking the leadership position of One Voice Mississippi, showing that the fruits from the Moses tree continue to blossom. Furthermore, one of Mississippi’s brightest young activists is Mac Epps who co-founded Mississippi M.O.V.E. and was a high school trainee for Southern Echo.

When my Pops died, neither I nor any of my siblings did any prolonged crying or sadness because he had given us all that a father could give his children. We are left with wonderful memories and lessons that drive and comfort us even in his absence. The same is true of Bob Moses. He gave all that a leader of love and justice can give. He taught people how to love themselves. He taught how to see greatness in common people. He taught students how to teach others. He taught how to organize. He taught the difference between organization and mobilization. He taught how not to quit. He taught people how to work with others with whom they may not always agree. He taught how to part in love. He taught how to listen to others. He taught how to be present for oneself and for others. He taught how to disagree without being disagreeable. He taught how to stand alone, how to stand with others, and how to know when to do both. He taught that no force is greater than the trinity of self-love, determination, and diligence. Ultimately, he taught that love is greater than hate and that black people are a beautiful and powerful mosaic that makes life beautiful and powerful.

*C. Liegh McInnis is a poet, short story writer, retired instructor of English at Jackson State University, former editor/publisher of Black Magnolias Literary Journal, and author of eight books, including four collections of poetry, one collection of short fiction (Scripts: Sketches and Tales of Urban Mississippi), one work of literary criticism (The Lyrics of Prince: A Literary Look), one co-authored work, Brother Hollis: The Sankofa of a Movement Man, which discusses the life of legendary Mississippi Civil Rights icon, and former First Runner-Up of the Amiri Baraka/Sonia Sanchez Poetry Award. Additionally, he has been published in magazines, newspapers, and anthologies.